Flowerville, who takes her name from Leopold Bloom’s “erigible or erected residence,” has published a book of photograms with Corbel Stone Press.

has published a book of photograms with Corbel Stone Press.

Like other work from a press that values paper and typeface and image and ideas (see my thoughts on Richard Skelton’s Landings here), this is a book of almost transcendent beauty.

And transcendent beauty may be the subject of the book as well.

These images are called “flowers of abeyance.” They are flowers in suspension, flowers of, in the root sense, desire.

We desire what we don’t have.

We don’t have these flowers.

Realistic landscape photographs give us a sense that we are seeing the real thing. They make us forget Kant’s insight about das Ding an sich (the thing in and of itself), his assertion that we know flowers only through our intermediary structures of knowing. The act of representation, of re-presenting flowers as photographs is an act of knowing through chemicals and colors and papers and lenses. Realistic photos make us forget that fact.

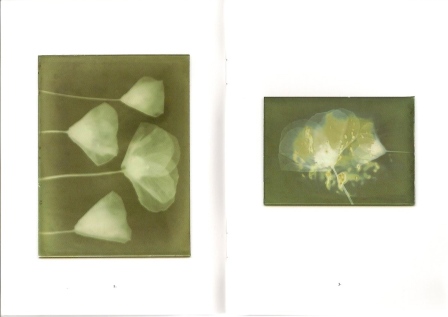

These are not such photos. Flowerville’s photograms are conjured on chemically treated glass plates. These are shadow images printed from the front and then again from the back, the back image slightly blurry when compared to the front one — a comparison a reader can make by turning from the odd-numbered page to the following even-numbered page: front and then back.

Here, for instance, are the somewhat blurry back image of the crisper front image on the preceding page (page 1) and then to the right a crisper front image (page 3) that is followed, if one turns the page, by a blurrier version of the same image.

Here, for instance, are the somewhat blurry back image of the crisper front image on the preceding page (page 1) and then to the right a crisper front image (page 3) that is followed, if one turns the page, by a blurrier version of the same image.

Why, I wonder, print both images? Why not double the number of images in the book by printing only the front image?

It must have to do with the idea of flowers in abeyance.

Together, the two related images highlight the presence of the glass plate. Together they assert that this is an image and not the flower. Together they infer that although they are not the thing, the thing may be lurking somewhere between or beyond them.

The haunting (yes, they haunt me) images are printed between excerpts from Amiel’s Journal, the first from December 2, 1851:

Let mystery have its place in you; do not be always turning up your whole soil with the plowshare of self-examination, but leave a little fallow corner in your heart ready for any seed the winds may bring, and reserve a nook of shadow for the passing bird; keep a place in your heart for the unexpected guests, an altar for the unknown God.

The images are nooks of shadow. Or, as the concluding excerpt from the journal says, they are creations, thoughts, acts of conception of a rare sort:

Sacred work of nature as it is, all conception should be enwrapped by the triple veil of modesty, silence and night.

If truth, as Nietzsche claimed, is “a mobile army of metaphors,” if truth is Leopold Bloom’s advertising patter, then we need another word for events of conception that are aside from or away from or below or within (the metaphors proliferate as they quickly reach their limits) truth.

We “see through a glass darkly,” as the Good Book laments (or celebrates?).

In Flowers of Abeyance, we see through a glass plate darkly (and lightly).

Transcendent beauty, always slipping away but there, on the next page of this book, waiting to slip away again for a reader in Zarathustra’s good night:

Die Welt ist tief, / Und tiefer als der Tag gedacht.

The world is deep / And deeper than the day had thought.

(thank you so much for writing this…)

a photographer mate once said that it’s not about recording an image, but creating it. i’m not even feeling i do that, it’s much more unconscious and in a way exactly expressing that sort of –

they aren’t so good as in (not selfdenigrating or so or maybe also), but they immanently aren’t so good, because they never will be so good, they’ll never be there as they are, in abeyance

and the 2 sides, that’s sort of blur and focused and how focused can you get… and does not blur tell you something else… and that it’s not about sort of getting as many images, but also perspective, is one thing seen from a few sides, (maybe that’s why i tend to be serial at times with images) and the same thing is of course never the same thing…. maybe a homage to the inexplicable, the not yet there in all its invisible unthought beauty, in a humility of the very eckhardian sense of Gelassenheit and etwas sein lassen [in its many appearances (and hinting at those appearances, at the never-quite-there)] about which Heidegger wrote so wonderfully, a celebration of possibility (as such).

(and that whole transcendental deduction, transcendental unity of apperception is such a beautiful thought… )

‘But there is one thing in the above demonstration of which I could not make abstraction, namely, that the manifold to be intuited must be given previously to the synthesis of the understanding, and independently of it. How this takes place remains here undetermined. For if I cogitate an understanding which was itself intuitive (as, for example, a divine understanding which should not represent given objects, but by whose representation the objects themselves should be given or produced), the categories would possess no significance in relation to such a faculty of cognition. They are merely rules for an understanding, whose whole power consists in thought, that is, in the act of submitting the synthesis of the manifold which is presented to it in intuition from a very different quarter, to the unity of apperception; a faculty, therefore, which cognizes nothing per se, but only connects and arranges the material of cognition, the intuition, namely, which must be presented to it by means of the object. But to show reasons for this peculiar character of our understandings, that it produces unity of apperception a priori only by means of categories, and a certain kind and number thereof, is as impossible as to explain why we are endowed with precisely so many functions of judgement and no more, or why time and space are the only forms of our intuition.” §§17 pure reason

LikeLike

i love “peculiar character of our understandings” you explore in this book.

LikeLike