Paris, 30 August 1997

“Louis Quatorze est mort en . . . en . . . en . . .”

“Oui! Oui! Oui! Oui!, says the old man’s friend quickly, hoping to forestall a lecture.”

It is my last day in Paris, and I don’t yet know that Princes Diana will die tonight, so as I continue up the Rue des Abbess toward the Montmartre Cemetery I don’t think about her, but about the Sun King.

He died in 1715, I could have told the Frenchmen. Yesterday, in the Louvre, I wandered into a palace room hung with tapestries depicting “L’Histoire du Roi.” They were woven at the Gobelin works between 1667 and 1672, and thus necessarily dodge the question of the king’s death. Instead, the huge wall hangings glorify that celebrity of celebrities.

In the seventh of the series, for instance, the King sports high-heeled boots with satin bows. Courtiers stand amazed, mouths open. One of them adjusts a 17th-century pair of glasses to see the King in all his glory.

In another section of the Louvre, I again find Louis in high heels (red heels and red bows), this time in Rigaud’s portrait done in 1701. Revealed and framed by a drawn-back ermine cape, muscular legs encased in white stockings rise up from the shoes, powerful columns that announce this king’s steadfastness, his ongoing victory over the entropy that finally lays us all low.

I sit down in a little park and pull out Sam Levin’s photo of Brigitte Bardot, bought from a rack near Sacre Coeur. Bardot, also standing on high heels, has lifted her skirt to reveal legs as brilliant as the Sun King’s. She manifests a stylish verticality, an enduring youthful uprightness, celebrity in all its seductive power.

“She’s acting as if something were wrong with her bo-w-el,” says one thick-legged woman to another as they pass my bench.

“Paris,” writes Malte Laurids Brigge at the beginning of Rilke’s 1910 novel, “is a good place to die.” This morning I woke up in my claustrophobic hotel room thinking of that line, not yet knowing about the coming night and the paparazzi and the tunnel, and decided to spend the day in the Cimetiere Montmartre.

As I walk through the gate into the cemetery, it begins to rain lightly. A map hangs behind glass with a table of celebrities. Pasted over one full quarter of the map is a hand-written sign: FOR “JIM MORRISON” GO TO THE CEMETERY “PER LACHAIS.”

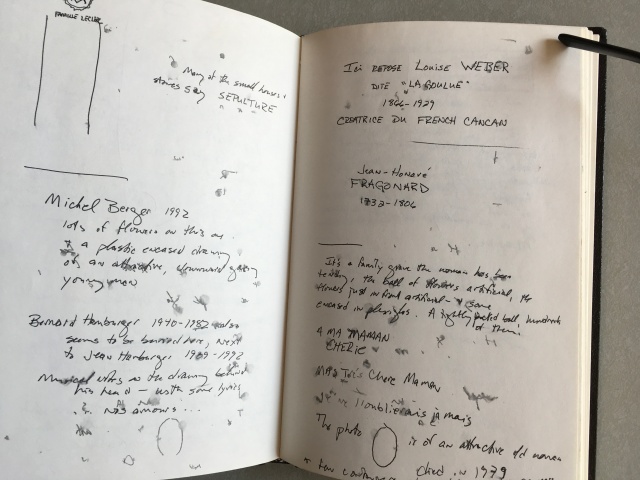

I read through the alphabetic table, taking notes on locations: Dumas: 21.3, Fourier: 23.2. Fragonard: 21.4. Bodies filed like books.

“Who was Jim Morrison?” asks a woman behind me. “A rock star,” answers an uninterested man.

My list complete, I set out to visit this cemetery’s famous inhabitants.

Heinrich Heine is first, that romantic and revolutionary German poet who wrote a workers’ poem so strong in its three-fold curse of those eternally recurring celebrities “God, King, and Fatherland” that simply possessing the poem was grounds for arrest in Prussia. A sappy bust on top of a square column, head reverently declined, eyes half-lidded; a cheesy harp with roses; and a sweet little poem about where will I be buried when I die: In Paris or Berlin? in the mountains or on a beach? buried by strangers or friends? no matter, the stars will still shine over me. Gag me with a spoon.

If monumental burial is intended to lend immortality, why are Herr and Frau Heine stretched out horizontally? Why not bury them upright in the square column. “Bury me standing,” the gypsy says, “I’ve spent my life on my knees.” Because, perhaps, after a lifetime of struggle we like the idea of resting, finally, in peace: Ici repose. . . .

Ici repose Hector Berlioz under a shiny black marble slab and a flamboyant bas-relief bust, buried with both Harriet Smithson and Marie Recio.

Ici repose Vaslav Nijinsky. Not much room in this stone box for a dancer. Two photos in a painted wooden frame leaned soggily against the headstone: One of Nijinsky as a young man in coat and tie, hair parted severely in the center, the other of the dancer with a white-painted face and the hat and ruffles of a clown.

Ici repose François Truffaut. Flat black marble with no headstone for the elegant filmmaker.

A gaudy grave meant for Èmile Zola and Mme Alexandrine Èmile Zola, sweeping curves of red marble framing a noble bust. But the activist author of “J’accuse” has been separated from Mme Alexandrine, a sign says, and now lies with other immortals in the Pantheon. Immortality. The word itself is hyperbole.

Ici repose Alexandre Dumas Fils. The novelist gets a marble bed with recumbent statue complete with poet’s laurels and a heavy roof held up by four columns. Someone, however, has made off with most of his left big toe and much of his nose. Even stone can’t ultimately withstand the ravages of time (or of the impious).

Charles Fourier, fantastic prophet of harmony and early 19th-century socialism (“magnificent denunciations of exploitation and sham in family, society, church, and state”), is memorialized by a slanting stone that acts as the final page of his book: “Les attractions sont proportionelles aux destinees.”

My favorite among these luminaries? Ici repose Louise WEBER, dite “La Goulue,” 1866-1929, creatrice du French Cancan.

The rain has let up. I decide to walk across town to the “PER LACHAIS.” If I could foresee Diana’s last words tonight, “My God, what’s happened!”, I would place her in Morrison’s context: superstar cut down in relative youth. But I can’t, so I search for the grave of the man who urged me, in my high-school years, to “break on through to the other side.”

This cemetery is too large for any kind of quick overview. The sign touched by too many reverent fingers is blank where the name “Jim Morrison” and the site address ought to be. “Oscar Wilde” and “Gertrude Stein” are only slightly more visible.

It’s late in the day. I’m tired. Diana is worrying about what to say when Dodi Fayed asks her to marry him tonight. I wander among monuments and empty little crypts. The rain begins again.

“JIM ➔” is scratched onto the mossy side of a crypt. I walk in the direction indicated by the arrow, guided by an increasing flood of colorful graffiti: “Jim Morrison ist unser Gott”; “”Jim, je t’aime”; “the doors”; “The 27 Club.”

In the middle of the path ahead of me stands a big man in uniform. He signals with his arm. He blows a whistle. He shouts “C’est fermé!” Closed. It’s 6 p.m.

So I see Jim Morrison’s much decorated grave only on the postcards for sale outside the gate. A year later I will hear on NPR that “his” lease is up. “Unser Gott” will have to find a new home.

By noon tomorrow I’ll be in Cologne, Germany, where my friends Žarko and Anne will break the news to me about the once and future celebrity Princess.

[Published in The Salt Lake Observer, 28 August 1998]

Scott –

What a tremendous piece! The ecphrastic quality + present tense + time-loop glimpse of Diana is very potent. In fact, your piece points toward a kind of travel-essay – sly, opportunistic, empathetic – I think is likely to replace a lot of the facile memoirizing we see.

I wrote John Alley (of the U of U Press) that we’ll be passing thru in early Nov on our way to Mexico. I offered to do whatever readings/interviews/book signings/classroom visits he thought would help the Press, we will be in no hurry. Maybe we can have dinner?

Soon,

PG

*** TESTIMONIO #38

Six weeks ago – because of the new President’s thinking, twitchy, compulsive, binary thing that it is – we fled the country. Winners and losers and keeping score, that is what matters to him. So we drove five days south, to somewhere life is a lot more nuanced: Guanajuato mining country. Here, centuries of local thinking make for different values. More than any momentary defeat or victory, people respond to what they call El Aguante, a term both ordinary and rather hard to translate. Resolve? Steadfastness? Either word is way too highfalutin! Maybe you could call it Firmness of Purpose, as that is what it comes down to, a demonstration of willpower over time.

Willpower over time! That is what lets it loose, the relief I feel, after a week of Trump headlines. I go off visiting local places of power, landmarks layered with generations of worship. First, I visit Cañada de la Virgen’s archaeological zone, the northernmost pyramids yet uncovered in Mexico. They date more or less from 500 to 1000 CE: they began as a spinoff colony of Teotihuacan; they ended as an abandoned satellite of Toltec Tula. For archaeologists today, the Otomí who lived there dwelt in a kind of shifty cultural border, one that lay between the two most powerful pre-Aztec states to hold the Central Plateau.

Their principal monuments – I learn from Wikipedia – were sky observatories. With a symmetry aligned to the rising and setting of sun and moon, situated to dominate the river basin it occupied, their temples syncopated human life with sky events, both for nearby farmers and for the hunter/gatherer types that survived in surrounding semi-desert. Imagine how the site must have felt to those who lived in it! It was a raw outpost, exposed, at the very edge of a great power’s influence, surrounded on all sides by those dog-eating barbarians, the chichimecas!

The bus trip to the ruins follows a riverstone-and-cement road – fitted with gutters to prevent erosion! – through land kept in a state resembling, someone apparently hopes, what it was 1000 years ago. The Lajas River cuts through, exposing granite columns, encircling the ceremonial center. And suddenly you feel the different layers of devotion that brought the whole thing into being! Five centuries of stonemasons and hod carriers, of architects and shamans. Plus ten years of archaeologists jigsaw-puzzling rubble back together. Plus permanent maintenance in the form of removing wind-blown seeds from the mortar between the stones to prevent their becoming rubble all over again!

The site’s security measures enhance that feel of layered devotion. Visitors approach only in state tourism busses, in groups of a dozen or fewer, passing through two locked gates, uphill on foot for the last kilometers. Ravines begin exposing, a step at a time, that same severe alignment of quarried stone that even now, after fifty years, triggers a recognizable double-take in me: there it is. We pause at a sunken patio, take a lap around the circular temple of Ehecatl, Lord of Breezes, and climb one staircase after another. Until the altitude – a bit more than 7000 ft. – leaves me gasping too hard to manage the last stairs. I’m perfectly content to look at the fotos my wife will show me later.

Later that same afternoon, we head downtown to La Parroquia, to where El Sr. de la Conquista hangs on a wall. He represents the very first mestizo art form practiced in Mexico, that of sculpting the crucified Jesus in pasta de caña, a mixture containing marrow of corn stalks and tatzigueni, sap extracted from an orchid, to produce a material rather like potters clay. It was the only stuff in which the elaborate wounds and dying expressions beloved of 16th century Spaniards could be molded. Think of it! Ordinary cornstalk marrow mixed with the sap of a flower harvested only in May at Lake Pátzcuaro! The result is a material subtle enough to register painterly overtones inherited from Giotto. It is mestizo art in a single gesture!

And as such, it replicates the stubborn, irreducibly treacherous bundle of habits that North America really is. Therefore beware. While el Señor dangles from his nails in La Parroquia, skinny, shins nicked, blood gushing out from between two ribs, remember that he weighs only nine pounds. Remember, in other words, that whoever did sculpt him inherited pasta de caña technique from Puhrépecha warriors who devised it in order to mold war gods light enough to carry off in headlong flight when they lost a battle.

The pyramid and the cornstalk-marrow Christ represent a pair of worlds wildly different from each other. Still, because the pyramid zone survived 500 years as a site of worship – and because el Señor, as an object of worship, survived another 500 years – each by now is a lesson in patience, in sharing limited inner space with feelings both incomplete and prickly.

Each may be incomplete on its own. But between them, they represent survival. Viewed from our own moment – from our own 500 years away! – that cornstalk-marrow Jesus was merely the follow-up posture a pyramid had to assume to survive. The two merged like a pair of scissors, binary as Trump’s thinking! They were nothing but shape-shifter survival, an expression of willpower over time.

Beware monuments and people that we pray for. Or pray to.

Copyright 2017 by Philip Garrison

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

beware monuments and people that we pray to. travel writing at its best@

LikeLike